05 Bak (Beat, 拍) -2

‘Beat’ as a point of contraction and an expansion of space

As previously examined, the word "박拍," as in a musical beat, is formed with two individual characters. One means ‘hitting,’ represented by “手,” (meaning hand(s), read [su]), while another character “白” depicts the empty space between strikes and provides the phonetics of the character. The 白 part of the word illustrates the vibrating spatial waves, expanding and contracting like inhaling and exhaling, created between the repeated strikes. Two hands facing each other, colliding at points of impact, then moving apart—this repeated, uniform action came to symbolize the musical concept of ‘beat’ with the character ‘拍’. Additionally, as previously mentioned, the word’s meaning and the musical concept of 'beat,' developed within European musical traditions (including korean word ‘박’ as translation of beat) shows only to one aspect rather than encompassing the full meaning embedded within the character '박拍'.

The character "박拍" encompasses not only the stike itself but also the '운韻 [un], *rhythm’ that arises with it, that is, the space created as the hands move apart and expand, or the long sound waves/pitches that emerge from brief collisions. On the other hand, when examining the etymology of 'beat,' it is difficult to find additional meanings beyond the unilateral sense of 'hitting.' The origin of 'beat' in Middle English "beten" and Old English "bēatan" also carried the meaning of a repetitive strike and has maintained its original sense of hitting or striking something repeatedly to this day. Over time, it has acquired various extended meanings, such as 'to defeat someone' or 'to be completely worn out (e.g., 'I’m beat')', but essentially, it is derived from 'repetitively striking,' and the use of 'beat' in music seems to directly apply the general meaning of the word.

(*it’s best translated to rhythm but not exactly the ‘rhythm’ as what we know. It will be clarified later on or check the article number 2 in the series.)

Cyclic Time

박拍 (beat) is temporal markings, measurement of musical time' and thus 시時 (time) itself.

‘Our’ time travels from here to there and back again.

Whether it's 박拍 or beat, both are uniformly continuous collisions that serve as measures to gauge musical time. The continuous occurrence of 박 is not an infinite straight line on a vertical axis, as experienced and perceived through conventional musical education, nor is it a collection of single events repeating the same movement in place. An individual "박拍" forms a cycle of start-process-result, while a series of 박 collectively cycles into a larger unit of "박拍" through a unique rhythm. This collection of 박, cycling and repeating in a unique pattern, developed into the concept of 'meter' in Western traditional music. The quantitative indication of meter is represented by the 'time signature,' and a 'measure,' which denotes a section of the meter, is indicated by bar lines (or measure lines) falling vertically across the staff. The basic pattern of all measures—such as the accents of 'strong-weak-medium-weak' in 4/4 time, or 'strong-weak-weak-medium-weak-weak' in 6/8 time—repeats with each new measure.

The cyclic nature of time is not a symbol or metaphysical content but a very physical phenomenon, a reality that consitutes our very existantial experience. Day turns to night, and a new day comes; spring passes, and a year goes by until the next spring arrives. The cycle is not merely a repetition of the same. The same morning differs from yesterday's morning, and this year's spring from next year's. The rotation of the Earth creates the 박拍 of days, and its orbit around the sun creates the 박拍 of years. The Earth and celestial bodies, pushing and pulling each other while rapidly rotating on their axes and orbiting each other, create small and large measures of 박拍, continuously uniting our time into a cohesive set of flow. The measures of time we experience on Earth are thoroughly formed through tangible physical movement, given equally to all living on Earth, whether perceived or not.

The structure of time in Korean traditional music is intricately designed to directly follow the natural cycle, emphasizing its deep-rooted connection with the rhythms of nature, embodying the framework of time units such as a year and the changes of all things within that year. The rhythmic patterns are designed to capture these changes, represented by the 24-beat rhythm for the 24 solar terms (Jinyangjo), the 12-beat rhythm for the 12 months (Jungmori), and the 4-beat rhythm for the four seasons (Jajinmori). Each rhythm is basically designed so that the more beats it has, the slower it is, and vice versa; the slower rhythms detail the changes of a year, while the faster ones compress the flow of changes within a year. In the 12-beat Jungmori, each beat represents a month, whereas the 4-beat Jajinmori does not cycle through just January to April but represents one season per beat, indicating a shift in the scale and proportion of time.

According to Viktor Zuckerkandl, composer and music theorist born in Vienna, when discussing meter in Western music, the general schematic symbolizing time is an infinitely extending horizontal line. This line is expressed by dividing it into equal measures representing the beats.

When we talk about meter, first and foremost, we think of dividing the flow of time, that is, evenly distributed time markers, regularly dividing time into identical units. Its visual symbol is a line with marks cutting it into equal lengths. (...) We have observed that under general conditions, regular beats would be experienced as organized into several groups. This becomes clear when we count the beats, saying 'one, two, three, four,' and after a certain number, we start again at 'one.' (...) In other words, we are not just moving forward; in some sense, we are continuously returning.

Viktor Zuckerkandl, The Sense of Music

(Please note: This quote is an English translation of the Korean translation of the original text. The title of the book in Korea called ‘음악이란 무엇인가?’)

The cyclic nature of time, returning after departing and coming back again, and the cyclicity of musical time, are not only evident in Korean Jangdan and music from various cultures around the world but also in the concept of meter in Western music. However, Western music theory tends to dominate the mechanical structure of music through abstract numbers separated from physical reality, making it difficult to discover the geoscientific reality and truth embedded in musical time within today's Western music theory. Nonetheless, Zuckerkandl insightfully observed that the schematic expressing beats as a straight line "contradicts" the rhythm experienced empirically, highlighting a difference between theoretical understanding and the natural musical experience and reality perceived. Western music's beats also "do not just move forward" but "continuously return."

The Principle of Cyclicity of Time

While we discussed the cyclic nature of time above, it’s important to note, when understanding this concept, that the term 'cycle' in '박拍' describes the phenomenological appearance and does not represent the principle of '박' itself. We must remember that the underlying principle and root cause—specifically, why and how the cyclic appearance emerges—are what drive or manifest this 'cyclic appearance’. Every form has an intrinsic principle of movement that enables its existence, function or motion. A red car appears to us as a single state of the same red color, a fixed shade, but this color results from the way atoms constituting the material vibrate and the process of movement that absorbs and reflects light. The light bouncing off, appearing red to our eyes, is the frequency of light waves, which then travel to our optic nerve, allowing the brain to perceive it as red. Similarly, the orbits of 'cycling' celestial bodies are shaped by the action-reaction of centrifugal and centripetal forces, rather than the orbits themselves being the principles of movement. Thus, discussing 'cycle' as a phenomenological expression through intrinsic movement principles does not argue that the cycle itself represents the essence of the structure of 박.

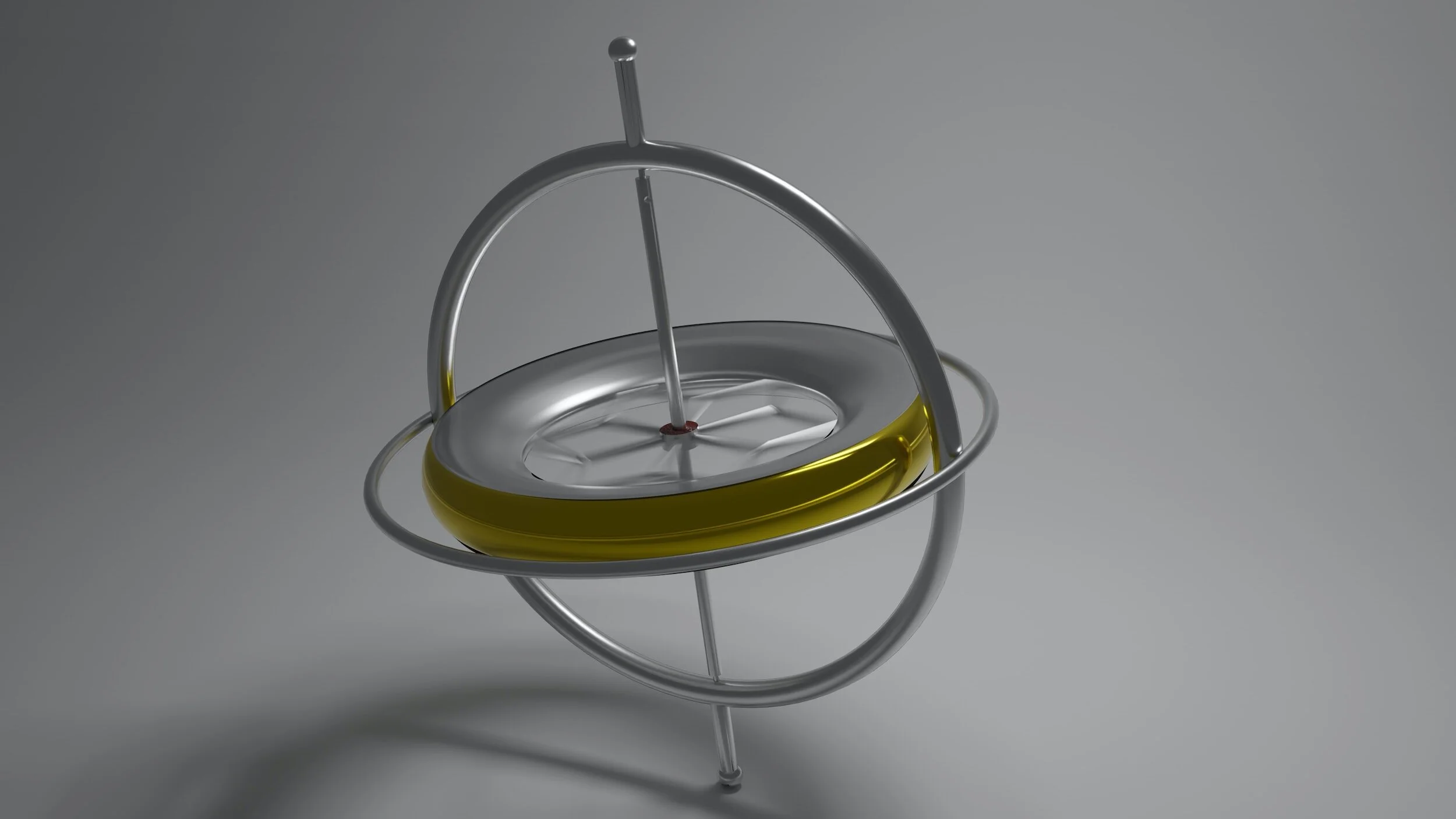

Imagine starting from one point and drawing a circle. Let's say we sequentially experience returning to the starting point after moving forward following the tip of a pencil drawing the circle on paper. This is akin to Viktor Zuckerkandl observing the sequence of experiencing beats, perceiving the cyclic nature of musical time. Now, let's imagine setting up a state where one point opposes another to draw a circle on paper. Without a compass, one might tie two pencils or sticks with a string to set the radius and draw. The bottom ends of the two pencils, or the sharp ends, must be firmly planted on the ground or paper, and the string representing the distance between the two pencils must be kept taut. The pencils can maintain their distance while moving in a circular motion only by acting centrifugal force while appropriately applying centripetal force. The pencils push and pull each other. It's through the action-reaction of these two forces that a circle is drawn. One appears to hold (centripetal force) while the other seems to be flung away (centrifugal force), but all these are relative perspectives, and ultimately, it's an interaction where both forces occur simultaneously. The direction in which one is flung is seen as the centripetal force pulling from the opposite side, and vice versa. However, differences in energetic density and strength exist, with one side typically acting as a rigid body. The cyclicity of time, in its essence, is a geometric manifestation of circular motion, reinforced by the interaction of centrifugal and centripetal forces. This principle applies to musical 'bak' (encompassing both beat and meter) and 'jang-dan,' the rhythmic patterns in Korean traditional music.

The ancestors who laid the foundations of what we now recognize as Korean tradition meticulously observed the celestial movements—driven by centrifugal and centripetal forces—and embraced these patterns as the basis for measuring time. They also understood this universal principle of cosmic movement as the nature of time. This principle underlies the division of ever-continuous time into measured units, such as calendars and '박' as the temporal markings in music, providing various Jang-dan patterns as temporal frameworks, such as 중모리, 자진모리, etc. The underlying nature of cyclic movement can be further understood by examining the concept of “Si 時, time”, the equivalent of bak (beat) in cosmic realm.

Gyroscopic precession also leads to a circular motion of 'going and returning' in one cycle of beat and rhythmic patterns, driven by centrifugal and centripetal forces, but the same motion occurs in individual beats as well.

What is Time?

Scholars may research the concept of time, which applies universally, but essentially, our time—whether perceived or objectively measured—is Earth-specific, with its definition and quantification being clear, distinct, and profoundly realistic. This is because it is established by the rotation and revolution of the Earth, the sun, and the moon.

The angle of the sun changes constantly relative to a specific point on Earth. It changes on a daily and annual cycle. From the perspective of a person standing facing south in the northern hemisphere, the sun rises in the east and its angle with the ground increases, reaching (nearly) a right angle at noon. This marks midday, when that specific area of the Earth's surface receives the maximum sunlight. As the sun sets in the west, the angle between the Earth's surface and the sun narrows, and the amount of sunlight decreases, leading to night. Additionally, as the Earth orbits the sun, it undergoes precession, leading to changes in the angle of its rotational axis. That is, the solar altitude becomes higher or lower, resulting in distinct seasons in regions with clear seasonal changes. In winter, the sun appears lower in the sky, so the angle of the sun's path (ecliptic path) to the Earth's surface is reduced, significantly decreasing the amount of sunlight during the day, while in summer, the solar altitude is higher, increasing the amount of sunlight. Near the equator, the solar altitude remains similar throughout the year, as do the seasons.

In conclusion, the paths traced by sunlight on Earth delineate temporal 'moments,' with the intervals between these paths constituting time. The character for time, 시時, directly represents these physical processes and phenomena.

Si (Time) and Bak (Beat)

Time (시時) is moments of the Earth, and beat (박拍) is the time of music. Si (時), or time, emerges from the interplay between the sun (日) and the earth (土), mirroring the foundational principle of bak, where the meeting of two hands (扌) symbolizes and signifies a moment in time. Despite their reliance on identical physical principles, they address distinct aspects of reality. Si encapsulates the temporal patterns fashioned by celestial dynamics, whereas bak embodies the temporal dimensions shaped by human actions, such as clapping or striking. This delineation highlights how both concepts, though rooted in the same natural laws, navigate through different spheres of existence—Si through cosmic motions and bak through human expressions of time.

Today, the distinction between si and si-gan seems not to be clearly made in our daily usage. Originally, 'si-gan' refers to the intervals, breadth, or sections of time, whereas 'si' denotes a moment as a point in time, a juncture. The character for time, 時, is formed by combining three characters: sun (日), earth and soil (土), and joint or knot distinguishing one from anther (寸). These three chracters together pictures a moment created at the point of collision where sunlight falls vertically onto the Earth's surface. The meeting of sunlight and the Earth's ground itself constitutes a 'touch,' which generates intervals and divisions (寸) in time. In other words, si means the point of juncture where a sunbeam (yang) pitching and hitting on the ground on the earth (yin) and the units created by it. The character 寸 (chon') might visually represent the point where a vertical line (longitude) intersects with a horizontal line (latitude), forming a spatial grid on the Earth’s surface. As described above, the word si itself defines what time is: section of time-space marked by the points created by the Sun and the Earth’s interplay.

If 'si' represents the Earth's rhythms or beats, then 'bak' is ‘si’ in music. Both 'si' and 'bak' inherently incorporate spatial dimensions, reflecting the spatiality of a sonic construct. The character for 'bak' includes 白, symbolizing 'empty space.' Meanwhile, 'eum-un,' or phoneme, combines 'eum' (note, tone, sound) and 'un' (rhyme or rhythm). 'Un' implies the expansion of sonic space, where 'bak' unfolds and 'eum' as in ideation of sound assumes tangible form. The word eum-un (phoneme), as the basic unit of sound, encapsulates its structural essence. 'Eum' signifies the initial emergence of sound—a condensed 'sonic seed' that conveys meaning/idea—while 'un' represents the ensuing expansion of sonic space. This space, soft and expansive, evolves from the compact 'eum,' unfurling the emotional 'flavor/taste’, much like a seed sprouting and extending through the soil. Additionally, 'eum' also mirrors 'si,' likening to a seed of solar ray cast upon the Earth to create temporal markers. Thus, both 'eum' and 'si' denote the points of collision of two forces that initiates the commencement of a new segment within the temporal-spatial continuum.

To say that sound itself encompasses spacetime, as does the beat, is no exaggeration. The 'beat' not only measures musical time but also serves as a gateway for individual sounds to emerge and expand into their unique spacetime with each moment.

The warp and weft of a loom: The warp is first strung vertically (north-south) to set the foundation, and then the weft is woven horizontally (east-west) across it, intersecting perpendicularly to create the fabric.

In fact, we generally think of time and space as separate entities. In music, it is customary to view and analyze the pitch and duration of notes as separable elements. While this is possible in abstract thought, in reality, the two cannot exist separately. Just as a fabric cannot be woven with threads stretched only vertically, horizontal threads (weft) must weave in and out of the vertical threads (warp) to create a weave. If the universe is a home built from the warp of time (時) and the weft of space or emptiness (空), then in music, sound becomes an entity where pitch and note duration/value are always intricately interlocked.

Similarly, when discussing 'beat,' the Western perspective often associates it primarily with temporality. However, it's crucial to recognize that a single beat arises from physical collision and resonates within space, echoing ('ul-i-da') as in the Korean sense of 'crying' or the way fabric or wallpaper might 'weep.' To frame it more vividly, one might say it presupposes that space itself 'cries.' It is true that a beat serves as a temporal marker, as its pulsation—repeating at a regular pace—creates intervals between moments in musical time. Yet, its essence also extends to space, as it spreads and unfolds, occupying our three-dimensional reality with volume. Therefore, fully grasping the beat's concept requires an integrated understanding of both its temporality and spatiality, offering a more holistic view of its role in music.