06 Center of Music

“Nothing exists without a center around which it revolves, whether the nucleus of an atom, the heart of our body, hearth of the home, capital of a nation, sun in the solar system, or black hole at the core of a galaxy. When the center does not hold, the entire affair collapses. An idea or conversation is considered “pointless” not because it leads nowhere but because it has no center holding it together.

The point is the source of our whole of wholes. It is beyond understanding, unknowable, silently self-enfolded. But like a seed, a point will expand to fulfill itself as a circle.”

— Michael S. Schneider (From “A Beginner's Guide to Constructing the Universe” (p. 54). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.)

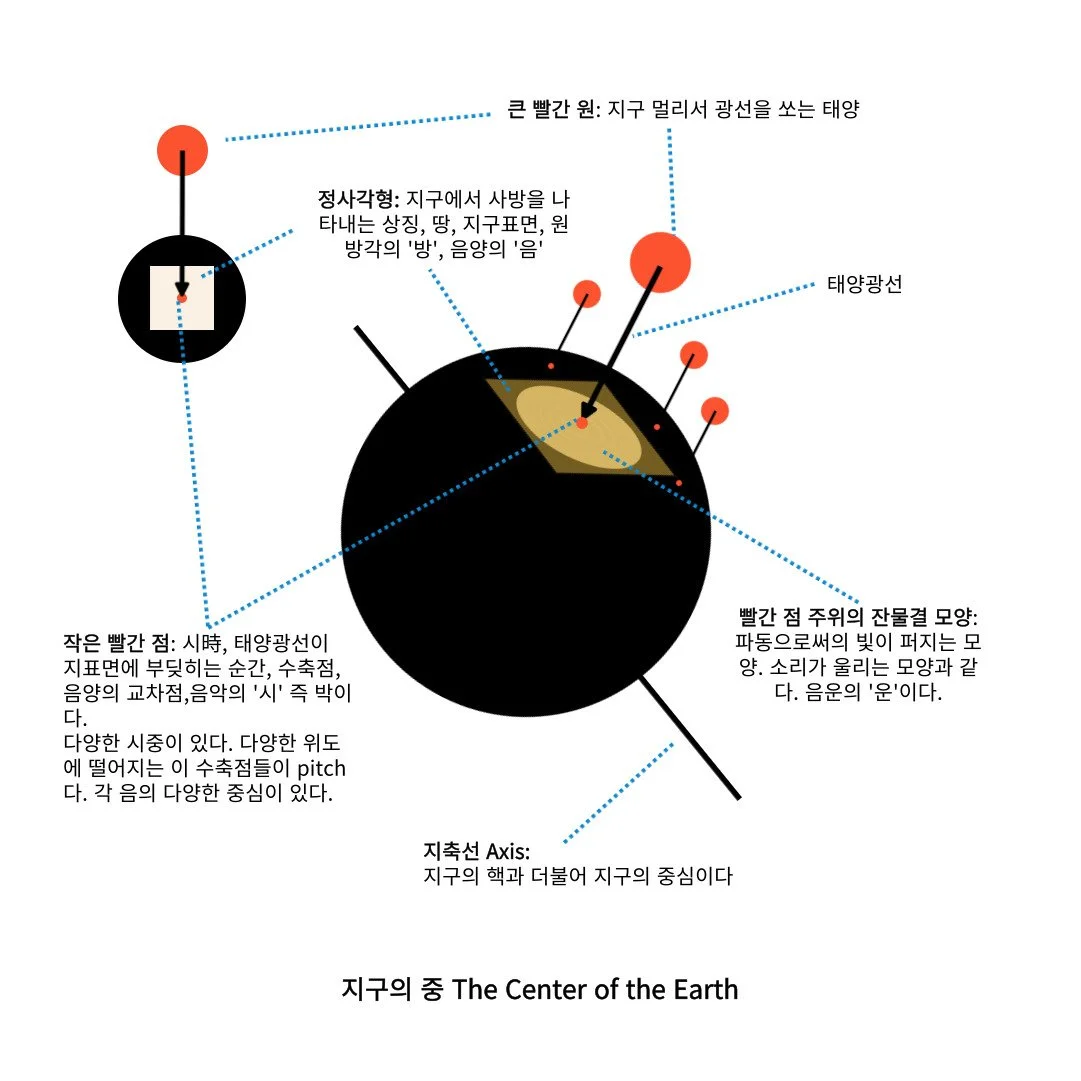

The character for "middle" 중 (jung) is a combination of the mouth radical (口) and the "to penetrate" radical (丨). Based on oracle bone script, this is interpreted as representing a flag planted in the center of one's territory, which geometrically can be seen as a line vertically penetrating the center of a square. The vertical line (丨) sets the upper and lower extremes, connecting these poles with a vertical and horizontal line to establish the center of a three-dimensional space. In the character 중, this space is depicted with the character for "mouth" (口), reflecting the ancient astronomical view of "heaven is round, earth is square" (天圓地方), which is, the traditional ideal measurement of space on earth.

Every existence has its own center. At the microscopic level, an atom is structured around a nucleus with electrons orbiting it; the nucleus is the atom's center. Earth's center is not just its core but also the axis it rotates on. The center of the solar system is the sun, which has its own axis. For humans, the heart and the spine that crosses the body's center from the top of the head are the centers. The center of an apple would be the line connecting the dimple at the top to the bottom, around which the apple's seeds are located.

Time is created by the motion of matter in space. These materials move in circles due to the interaction of centrifugal and centripetal forces, generating immense amounts of friction and energy, leading to various energetic interactions. In the realm of Earth, the sun and moon play a significant role, with the sun being likened to a father and the moon to a mother, and Earth to the womb within the mother. The center, where the father's sperm and the mother's egg meet to create life, becomes not just the axis of movement but also the field of all actions. Thus, "center" (중) is both the axis of physical movement and the time-space basis for action to occur, possessing a neutral quality.

Then, what constitutes the center of sound? Sound transcends merely being an observable physical phenomenon, capable of being quantified and measured. Beyond these sonic phenomena, sound encompasses the forces, mental and emotional motivations driving its creation and actions taken to generate the sonic vibrations. In exploring the essence of sound, we must consider both its tangible manifestations and the underlying principles that give rise to them. This dual approach reveals sound's existential significance, intertwining the observable phenomena with their foundational causes.

For example, consider the 'sonic phenomenon': when a drumstick hits a drum skin, it vibrates. This vibration creates pressure waves in the air that travel to our ears as sound. Beneath this observable event lies the drummer's intention, breath control, and the physical act of striking the drum—these elements constitute the 'root of sound.' The interaction between the observable sonic phenomenon and the underlying essence or cause of sound collectively shapes the entirety of sound's existence. The root cause, though invisible and lying beneath the surface, alongside the visible phenomena, forms the complex structure of sound. It's important to note that the observable aspects of sound are not the aspect that directly cause this interaction; understanding sound fully requires examining both the physical phenomena and the underlying principles.

Sound's structure is based on the interplay between sonic phenomena and their foundational principles, with a 'center' at its core. However, within this framework, there are endless essences and phenomena, continuously unfolding in a manner akin to splitting a magnet, which invariably reveals a north and south pole. Beyond this central point in sound's ontological structure, numerous other 'centers' can be identified, each contributing to a deeper understanding of sound's multifaceted nature.

Moreover, 'jung' (중) can also be understood as 'si-jung' (시중), or the center of time. 'Si-jung' represents a dynamic center that evolves over time. Nowadays, it is often used to denote the ability to adapt wisely to varying circumstances. Despite frequent news about shifts in the Earth's axis, it's essential to recognize that the Earth's center is in constant flux due to its precession and orbit around the sun. This means the axis itself rotates and revolves, making our planet's center a moving point.

The term 'si' (시), representing a moment in time, can be likened to a brief, intense ray of sunlight. The Korean word '살' (sal), meaning both 'ray' and 'arrow,' underscores this analogy, suggesting that 'si' marks the precise point where sunlight touches the Earth's surface. As the Earth spins and orbits, the way sunlight interacts with any given point on the ground shifts continually. Therefore, the 'center' within the vast, physical realm is never static but always in a state of transition, in motion.

The red dot symbolizes the sun and the small dots marks the exact point where a ray of sunlight touches the Earth's surface, embodying the Yang force. The black arrows depict the sun's rays extending outward from its source. The square signifies the Earth, representing the land and its four cardinal directions, encapsulating the Yin force. Surrounding the small red dots, which denote various 'si' moments or temporal points, are ripples. These ripples visually represent the oscillation within the time-space continuum, the vibrations of sound, and the resonance of phonetic sounds, capturing the dynamic interaction between time, space, and sound.

Every individual note possesses its own unique center. Considering pitch, the fundamental frequency serves as the note's core, with various harmonics resonating like enveloping tones. Modern music theory systematizes the identity of a note based on this fundamental frequency. While this method simplifies understanding and makes processing musical information more economical, it overlooks the richness beyond the fundamental—a detail both creators and listeners should perceive attentively. Appreciating music requires holistic processing, extending beyond cognitive understanding and analytic reasoning even if it is accompanied by a bit of sensual arousal. It necessitates deeper, patient engagement, acknowledging that the depth, timbre, mood, and texture of sound arise from these surrounding tones. These qualities make individual sounds distinct and unique, ultimately creating meanings in specific time-space contexts.

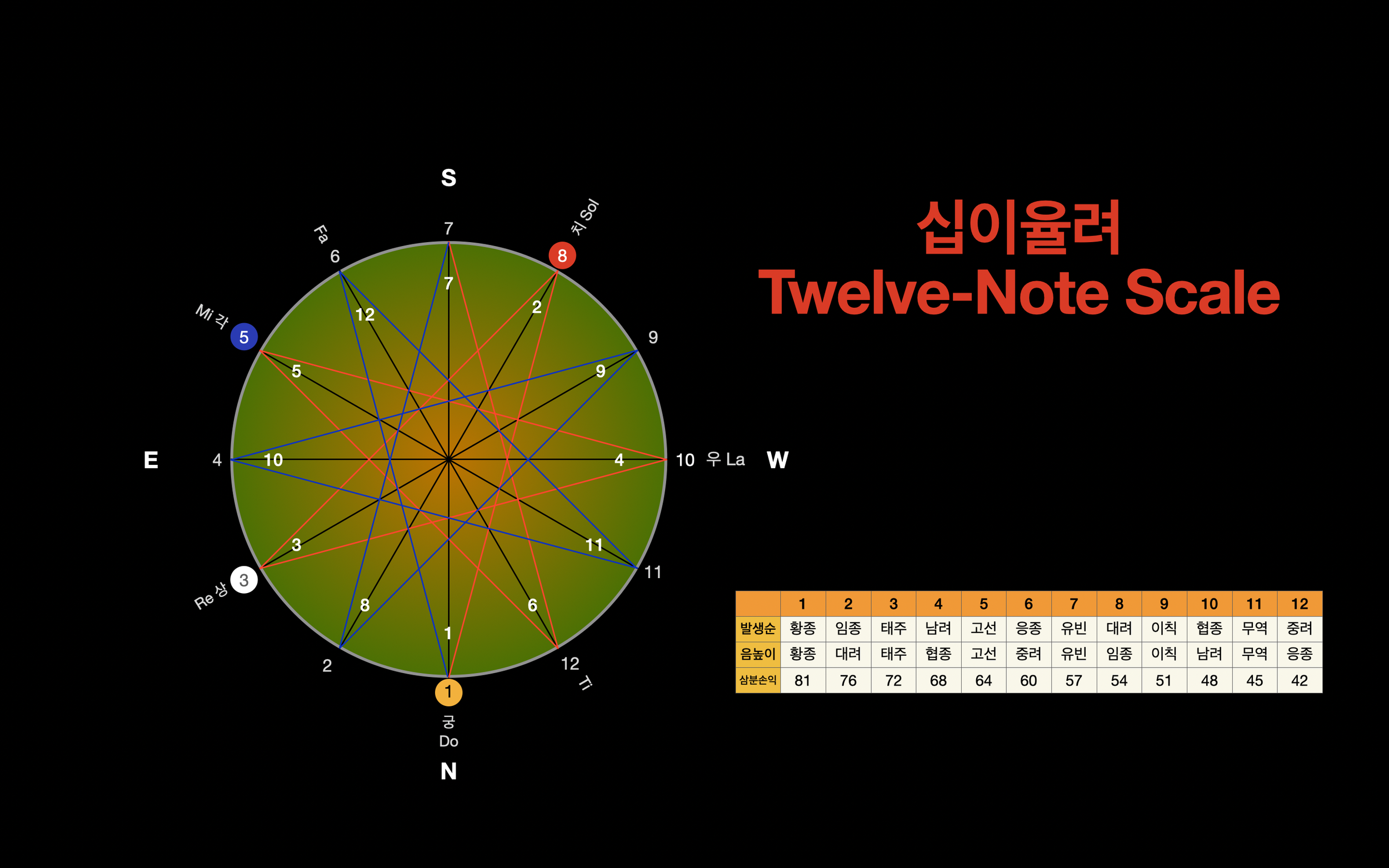

And these various sounds are essentially the entirety of the sound (note). A musical scale resulted of diversification of one central sound. In Eastern music theory, sam-bun-son-ik or ‘trifurcation by loss and gain’ method is applied to set notes in scale ‘gung-sang-gak-chi-wu’ and 12 yul-ryeo. Trifurcation process takes an initial note as the ‘central note’, the seed to the scale. This initial note called ‘gung’ has the value of 81, diminishing according to this trifurcation calculated ratio. The notes ‘growing’ out of the ‘seed’ note are produced by the interval of fifth. In the theory of harmonics, it’s known that the first overtone that is not in unison with the fundamental is the fifth above it.

Usually, the clarity of harmonics is enhanced with stronger force and pressure when played. Consider being in a room encircled by mirrors, shaped into a dodecagon. Directing a weak light beam at a mirror merely reflects it minimally. In contrast, a powerful beam can illuminate all mirrors from every angle. This analogy extends to sound production: stronger force not only amplifies resonance within an instrument's body and various resonating chambers but also enriches the sound with a variety of tones and textures. Thus, even a single note encompasses a spectrum of sounds, and the variety of 'shapes' within a single sound demonstrates the potential for diverse expressions within each note.

Keyboard instruments like the piano pose challenges in this respect due to their design. The colors of music in these instruments are supposedly created by combinations and blends of individually identified tones, not by amplifying the embedded harmonic colors within one note. Different levels of pressure applied to the instruments are intended for dynamics, volumes, or the loudness and softness of sounds, not for color. The structure of the instrument itself imposes this particular idea and perspective on what a sound or a note is, leading people to easily overlook the full spectrum of a single sound that could express various 'degrees, volumes, and geometries' of sound.

Thelonious Monk, known for his 'angular' sound, exemplifies this concept. His playing is marked by distinct pauses between notes, offering extreme clarity and definition of both void (non-sound or pause) and sound, not commonly found among his contemporaries. Rather than densely layering notes for sonic colors as a group where individual notes cannot stand alone to achieve the meaning of the chord, Monk's technique of striking individual notes, painstakingly and selectively chosen, produces a rich, meaningful sound. This approach results in a fuller musical experience with fewer notes, emphasizing the importance of robust execution. This interpretation of sound, focusing on the central and surrounding tones, aligns with a broader, more nuanced understanding of harmony, distinct from conventional theories of chordal stacking.

“1” encircled in yellow, the initial note acts as the foundation for generating the subsequent 12 notes. The numerals inside the large circle display the order of derivation via a trifurcation method. Once these 12 notes are sequenced by ascending pitch, as denoted by the numbers outside the large circle, they compose the chromatic scale, as known in Western music theory.

This diagram originates from "Akhak Gwebeom," a book published during the reign of King Seongjong in the 15th century of the Joseon Dynasty. It not only depicts the 12 yul-ryeo (12-tone scale) and the five notes (gung-sang-gak-chi-wu) but also aligns with the 24 seasonal divisions, which include the summer and winter solstices, and the equinoxes, as well as Eastern astrological symbols. This illustration underscores the connection between the macrocosm of the world and the microcosm of musical phenomena, suggesting that the universal 'rhythm' influences and provides a structure for these musical expressions to mirror cosmic patterns.

Let's revisit the room with mirrors arranged into a perfect dodecagon. When we emit a ray of light from one side, it would fail to reach the directly opposite side. This discrepancy occurs because, as the light journeys, the room itself is in motion, rotating and revolving. Contrary to common perception, sunlight's journey to Earth spans more time than expected; far exceeding a mere blink, it takes roughly 8 minutes. Therefore, the sunlight bathing us at any given moment embarked from the sun 8 minutes prior. Consequently, the angle between a specific Earth location and the sun at the instant the sunlight is emitted, and the angle upon the sunlight's eventual arrival on Earth's surface, alters due to Earth's rotational and orbital movements. This results in the sunlight landing on a slightly different Earth location than anticipated, explaining why the lines in the above diagram veer slightly off-center. This is a principle called "Geok-Pal-Sang-Saeng," a term suggesting a division into eight parts that mutually support each other.

A significant aspect of note generation adheres to the interval of a fifth, akin to principles found in Western music theory. The initial five notes derived from the ‘central note’ or fundamental frequency, when sequenced by pitch, create the pentatonic scale. By applying the method of "trifurcation by loss and gain," and continuing until a note matching the fundamental is reached (an octave higher note in unison), a total of 12 notes emerge, forming the complete scale. Furthermore, this process ensures that the progression of note generation maintains intervals of fifths. Notably, the relationship between the second harmonic of the fundamental note and the first uniquely different note being a fifth apart is an important consideration.

Within a single musical piece, the center of sound varies with each individual note. In phonology, 'eum' corresponds to concept of 'si,' (introduced in detail in articles for ‘bak’) and the center of this sound changes constantly. Thus, 'si-jung' (時中) is essentially 'eum-jung' (音中). Simultaneously, within a single musical composition, not just individual notes but the entirety also has a center. This center is what is referred to as 'cheong', 'jo' (scale), 'tori' in traditional Korean music, or in Western terms, 'key', 'tonality', or 'mode'. While the terminology varies with the cultural context and structural approach to music, each term denotes a central standard in terms of pitch. In Korean music, 'jo' represents not only the central position in terms of pitch but also encompasses the overall mood and emotional direction of the piece, offering a comprehensive concept. Conversely, major and minor scales in Western tonal music, as well as the various modes of medieval Western music, each convey different atmospheres and colors. However, in tonal music, major and minor scales are not defined beyond their mathematical properties.

Zuckerkandl interprets the concept of 'key' as "it is not merely about a single note acting consistently as 'one' throughout a composition. Instead, it implies that the movement of the center is not arbitrary; there is an underlying force, a 'center within the center,' which will manifest in some way. This 'center of centers' is the prime note of the scale." In this statement, Zuckerkandl emphasizes that the tonic, serving as the first note in sequence, acts not just as a starting point but as a central axis or core, closely aligning with the ancient Greek concept of 'the one' (monad) and the Korean numerical concept of 'one'. The center varies depending on the singer or the individual instrument, even within the same song. This variation is also an instance of 'si-jung' and the center of music.

Sound travels in three-dimensional curvatures rather than in a linear fashion, occupying a voluminous space with dimensions of up, down, left, right, forward, and backward. It is akin to the ripples created by a stone thrown onto a lake's surface, involving not only the concentric circles on the water's surface but also the vertical movements that ripple through it. This analogy encompasses not only the outward spreading concentric circles upon the water's surface but also the intricate vertical oscillations that permeate through the entire body of water. There exists a central point or jung in terms in every note varied in pitches. Additionally, we can find jung of sound in the process itself by which a note resonates and spreads. Using the ripple analogy yet again, the precise point at which the stone breaches the water's surface and descends, initiating the ripples, serves as both the temporal heartbeat and the rhythmic core, center or jung of the note. This center is not merely a point in space or a moment in time but a nexus of connection, symbolizing the note's fundamental essence and its interactions within the cosmic tapestry of sound. It reflects a deep philosophical understanding that each note, each sound, is a microcosm of the universe's interconnectedness, resonating through the fabric of existence and echoing the universal symphony of life.

In one Jang-dan cycle, each beat carries its own center, yet what constitutes the center of a rhythmic cycle as a whole? It can be argued that the first beat holds this central position. In Western music, a single note or beat has traditionally been perceived as incomplete on its own. At least two consecutive notes are needed to create a melody with musical meaning, a principle that applies equally to the concepts of 'beat' and 'meter'. The concept of meter, defined by a particular arrangement of accents and a specific number of recurring beats, cannot be understood through just one beat. The identity of a meter, in western orientated music theory, is revealed by how beats form a collective.

However, in traditional Korean music, the first beat of a Jang-dan encompasses the identity of the entire cycle or period. As long as Earth's rotation and revolution continue, welcoming January of the new year means understanding the identity of all 12 beats (months) that will unfold. Each year's first month is the beginning that bears the potential and identity of all four seasons and 12 months ahead. January is the seed month, the point where Yin and Yang are fully contracted and collide, akin to the first beat in a rhythmic pattern.

To summarize, every "jung" or center is a core akin to a tiny contracted point and the axis around which it intersects or rotates. The center of a musical note, as a sound, is the moment of the 'beat' that each individual note possesses and the fundamental note that represents the pitch of that note, including all harmonics within it. Additionally, in Korean traditional music, this fundamental note is not a single sound but encompasses and represents the melody derived from it, acting as the seed and root of sound, songs, and musical pieces. The center of a note changes constantly. The countless notes in a piece of music continually change in pitch and the timing of their performance. Meanwhile, the myriad melodies in music arise according to the center of each performer. Furthermore, musicians around the world sing and play with their own individual centers.