01 Mass and Velocity

Understanding the principle and workings of sonic manifestations produced by all subjective entities. [CLICK HERE TO READ THIS ARTICLE IN KOREAN]

Two of the most famous formulas in physics discuss the relationship between force, mass, and velocity. The Newtonian definition of force is mass times acceleration force (F=ma) and Einstein's definition of energy is mass times the speed of light (E=mc2). Music is composed of the motion of sound. Sound does not stand still but constantly moves, manifests, and disappears. In this first FfT newsletter article, we will take a look at mass and velocity as two major factors of sonic manifestation.

In Newton's and Einstein's formulas, force is expressed as an object with mass and speed added to it, and that mass, as I define it, is an entity. Because every individual being operates with its own center, we define each as a 'subjective entity'. The magnitude of the force exerted by this individual subjective entity is dependent on its mass and speed. In music, this individual entity can be called a note. Therefore, all sounds are forces created through the workings of mass and velocity.

The process of sound manifesting is not entirely visible. Manifestation is the result of the workings of invisible forces. Specifically, it pertains to the reaction of invisible forces (actions) as if a driving motivation generated inside one's mind led to one's action or a the mechanical workings in the back of a clock displayed time with hour and minute hands. The hidden side of manifestation is called 'che體' and the manifested reality is called 'yong用'. Traditionally, in the East, especially in Korea, 'che-yong' has been understood and reasoned as an organic and dynamic relationship between the essence and the phenomenon. Yin-Yang is not a fixed and dualistic metaphysical concept, but a physical movement and relationship that is the result of the cross movement of two opposite forces.

Music refers to the whole of an event that is revealed to the phenomenal world as sound. It is impossible to separate music as a phenomenological event from its 'subject' which is the root of its manifested form that we can perceive. In other words, a subjective entity acts as 'che', and music comes out as a reaction to its action, which is in the realm of 'yong'. Further, subjective entities that perform music, the time-space where it is performed, and the audience that occupy the time-space all belong to the specific time-space.

I would like to step back from our comprehensive discussion of music ontologically for a moment and discuss what happens to performers at the stage of 'che'. A performer's force is converted into sound energy, resulting in a single sound, which is superimposed and connected in time and space, becoming a phenomenal event called music. Essentially, if the instrument is a fixed medium, then it is the player's responsibility to adjust and articulate it (or shape the sound). In spoken language, we adjust and move our tongues and lips against our bony palates and bones in our jaws. Simultaneously, this phonetic articulation is done by controlling the pressure of air traveling through the articulators with our breathing.

With physics formulas, it would be almost impossible to express the multitudes of sonic shapes and their aesthetic values. There is, however, a way to express the "strength-softness" of sound, or 'force' proportionally working through (air) pressure. Imagine playing the piano, for example. By raising your arm and elevating your hand, you can increase the potential energy of your arm and hand. It may be relatively easy for someone with thick arms and heavy hands to make a loud sound. Hands themselves are already heavy, so they are larger in mass. If your arms and hands are small and light, raising your hands high to increase potential energy is another way to play. When it rides gravity as much as possible to reach the target point, the hand will act on the keyboard without almost any loss of potential energy. If your hand hesitates while falling, you will lose the power of the potential energy that is converted into acceleration when you fall to the target point. Taking the acceleration force to the target point with confidence is the key to playing a solid sound. (Strength-softness is a direct translation of '강유', a word formed with two individual and contrasting words meaning hardness and softness .)

In vocalization, the strength of the sound depends on the amount of air pressure applied to the vocal cords. In fact, air pressure itself is not an object with mass; but it is an action of force in time-space, which has a beginning and an end. Thus I want to interpret it as an individual entity as well. When air pressure moves in a certain direction, it causes the vocal cords to vibrate and produce sound. Air pressure is converted into sound energy. When air approaches the vocal cords, the pressure exerted increases rapidly.

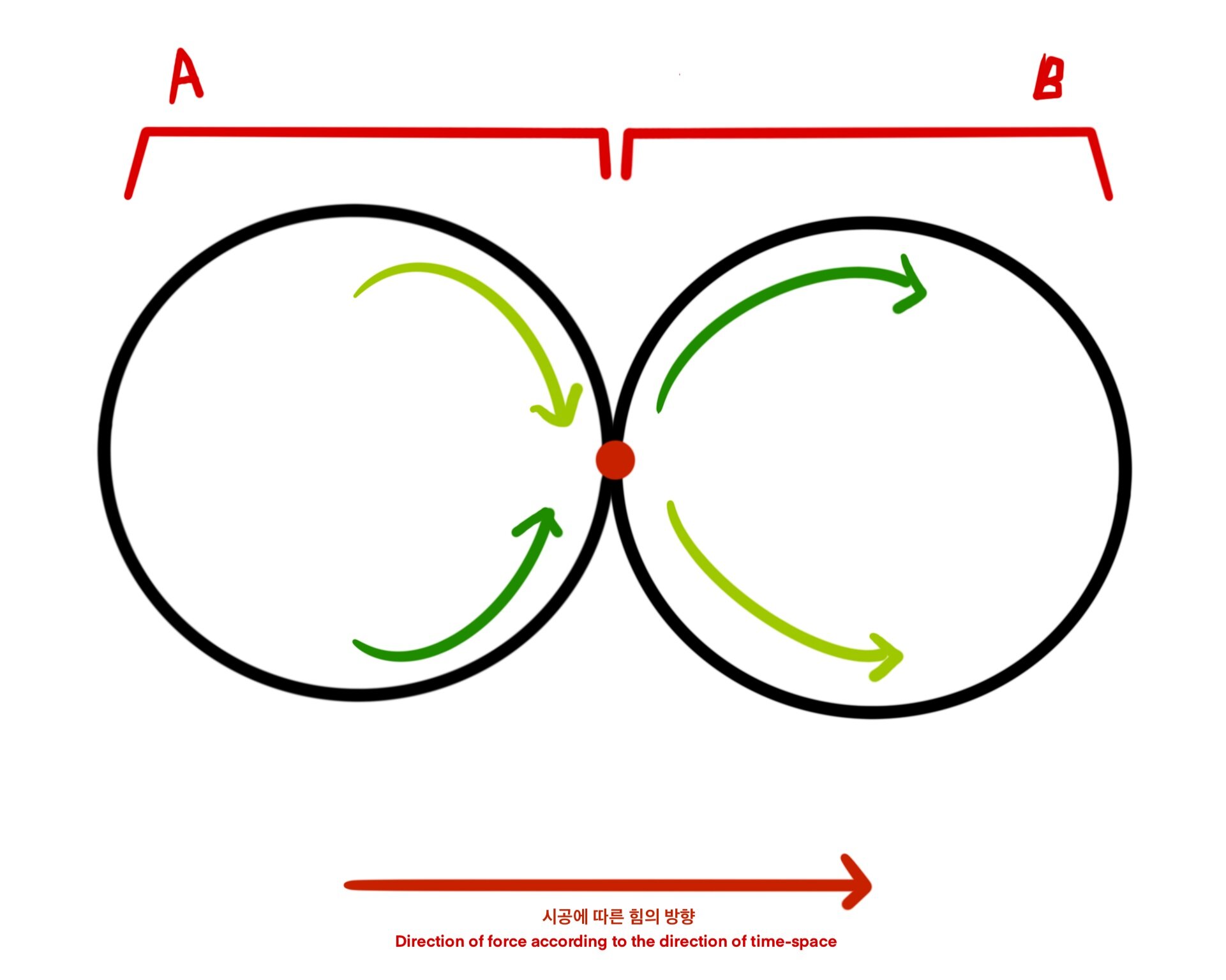

A = Che, essence, B = Yong, phenomenon

A = Inhalation, B = Exhalation

Red Dot = Point of Contraction, Collision

Red Dot = Eum 음音 , B = Un 운韻

Red Dot = Dan 단 (short), A & B = Jang 장 (long)

As you can see in the diagram above, part A corresponds to the 'che' before sound is revealed, and part B corresponds to when sound manifest. There are several motion processes that occur before sound is generated, and B shows the direction in which sound energy moves after the red dot. The red dot in the middle represents the moment when air hits the vocal cords or a finger hits the key, followed by a hammer striking the string. Yellow and green arrows indicate how the distance between the two poles changes. For instance, it illustrates the following: you lift your hand, the piano keys and the hand move away from one another, then collide again. With the two poles pulling together and meeting, acceleration is added, and with the sound coming out, the speed gradually slows down and the two poles separate. When the red dot is reached, the air density reaches its peak. Then, the air density also thins out as sound gets projected back into the open air.

This is what 'jang-dan' and 'ho-heup' are. Initially, the opposite ends are far apart, then they come closer, and the centripetal force acts, quickly contracting, and eventually, they collide. This collision is 'dan' (short). Jang-dan, the contraction and expansion of time-space, is the principle that works throughout in the areas of breathing, sound production through musical instruments, Korean traditional music and more.(Jang-dan literally means long-short; ho-heup means breathing or breath. Ho-heup is a combination of two words, inhalation and exhalation.')

In the graph above, the red dot represents 'dan' and the two circles represent 'jang'. With respect to part A (che), 'jang' moves from 'jang' to 'dan' under the influence of centrifugal motion, whereas 'jang' of part B (yong) expands under the influence of centrifugal motion. Proceeding with this process further, (B) will become the 'che' of another 'yong' (B').

As such, energy or force circles back. Seon-yul (melody) is the word that describes this physical exercise of melodies precisely. Seon of seon-yul is not seon (線) meaning lines but seon (旋) meaning circling backwards and rotating. The two poles at opposite ends collide and produce a point of sound; the contracted point of sound expands and the two poles within the sound move far away from each other. As the sound gradually loses the initial power that pushes it toward the open air with high velocity, the two poles circle back to the point of contraction, intersection or collision.

Nowadays, the image of 'lines' seems to be the general perception of musical melodies. Melodies that assemble the image of lines are like narrow streams of water that have no volume, simpler than 2-dimensional geometric shapes. Originally, seon-yul, or melody in Korean, signifies sonic shapes with volume and circular motions flowing across (more than 3-dimensional) time-space, and diversified sounds comprising high-low and long-short tones.

Melody, regardless of whether it is in the east or west, is usually defined as a combination of pitch and rhythm. Rhythm shares the same etymological meaning as rhyme in literature and linguistics. In the graph, the contracted point expressed with the red dot is 'eum音' and the part B where the 'eum' expands with circular motion is 'un韻'. In phonology (it is 'the study of eum-un' in Korean), one syllable must have a vowel accompanying consonants. In Hangeul, the initial and the final (both consonants) act as the seeds leading to the articulation of 'eum'. As 'eum' acts on the vowel, which is like a longitudinal line, it will resonate and reverberate for a prolonged period of time. This is 'un韻'. 'Eum' happens in a flash, but 'un' can be elogated. Thus Un is long and Eum is short. Eum is where two opposite forces collide, and Un is the long ringing sound created by that collision.

After a collision, they spread out rapidly at first, then their speed gradually decreases as they move away from each other. The greater the force or pressure applied to the instrument or vocal cords, the more intense the collision at the point of contraction. In a strong collision, the force is proportional to the mass (potential energy) and speed of the two objects. Depending on how much force is applied to the contraction and point of impact, the distance and range of the sound will grow. The density, pressure of breathing for a singer or a blowing instrument player, the tension of the string or membrane of the instrument for an instrument player, the weight of the hand or bow, the distance between the instrument and the hand or stick that imparts force to the instrument, and the resulting potential energy : all of these are the factors that contribute to a strong collision.

These equations relate the dynamics of mass and velocity across all facets and phenomena related to sound.

To follow up on today's content, next week's newsletter article will discuss how "gi-un-saeng-dong" can be achieved through the principle drawn from physics discussed above and its significance in terms of the aesthetic value. It is greatly appreciated that you read this entire article.